by James Kraus

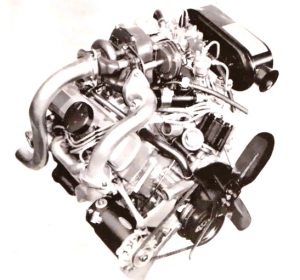

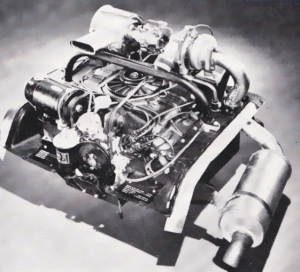

1962 F-85 Jetfire 3.5 liter turbocharged V8 powerplant

Though still most commonly associated with diesels, turbochargers on petrol engines are once again proliferating, and with increasing emphasis on fuel efficiency, it is likely they may well be here to stay. The main reason they are becoming popular is that they are a natural fit with direct fuel injection, which is becoming ever more affordable to manufacture. One of the historical drawbacks of a turbocharger installation on a petrol powerplant has been their propensity to detonation.

This was historically held at bay by drastically lowering the compression ratio of the engine. Unfortunately, this correspondingly dropped power considerably, until the deficit could be made up by the boost pressure of the turbo as engine speed increased. This was the cause of turbocharged spark-ignition cars suffering from turbo lag, feeling lethargic at low RPM and often producing less than stellar fuel mileage.

With direct injection inserting fuel only at the moment needed (as in a diesel) the threat of detonation is virtually eliminated, and compression ratio of present direct-injection petrol turbo engines are in the same range as equivalent normally-aspirated versions. Currently, there are virtually no disadvantages to adding a turbocharger other than cost, complexity and a small weight gain. With the addition of turbocharging, engineers can choose to increase power, improve fuel efficiency or pursue a blend of both goals.

I thought it worth a review of the first turbocharged cars ever offered, which are now all but forgotten. Other than being General Motors products, having turbochargers, side-draft carburettors (quite rare in the U.S.) and four wheels, the cars shared little in common. They were vastly different in both overall design and their approach to forced induction.

Turbocharged F-85 Jetfire rocket-motif logo

First came the Oldsmobile F-85 Jetfire. It went on sale in April of 1962, just a few weeks after an obscure musical group called The Beatles were first heard on BBC radio.

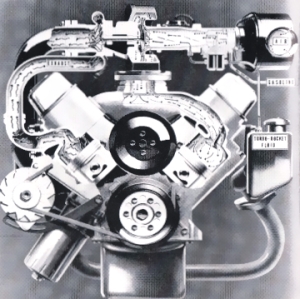

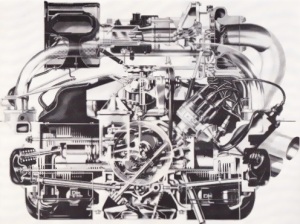

F-85 Jetfire engine cross-section

The F-85 was a front engine, rear drive coupé. In its new Jetfire guise, it was given a fairly small 63 mm Garrett-AiResearch turbocharger operating with maximum boost, limited by a wastegate, of a quite modest 0.35 bar. This low-pressure approach to turbocharging was more recently used by Saab in their 2.3 Ecopower engine. The turbo was mounted to the Oldsmobile version of the Buick (later Rover) aluminium 3.5 litre V8. The aim of the engineers was to increase torque across the rev range with no sacrifice in fuel economy. To this end, the standard engine’s high 10.25:1 compression ratio was retained. Compared to the normally aspirated engine, horsepower was increased by 16%, torque by 30%.

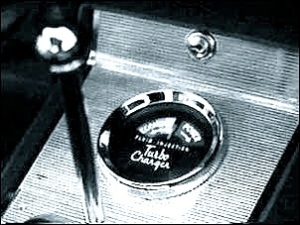

World’s first automotive turbo-boost gauge, later to become an aftermarket best seller

To prevent detonation with the high (even by today’s standards) compression, water injection was used. The actual elixir (available from the local Oldsmobile dealer) was a mixture of water, alcohol and a corrosion inhibitor marketed as Turbo-Rocket Fluid.

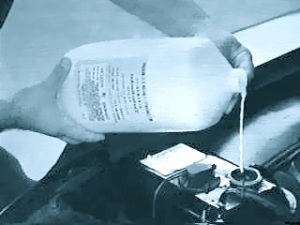

Replenishing the Turbo-Rocket Fluid storage tank

This was stored in a five-quart reservoir in the engine compartment and injected any time the boost pressure was positive (under acceleration). Because of the severe risk of detonation associated with such a high compression ratio, the reservoir was fitted with a float that when near empty, would activate a warning light on the instrument panel. If allowed to run completely dry, a sensor on the float would divert engine vacuum to a diaphragm that would partially close a second throttle butterfly located just downstream of the carburettor. This prevented the engine from being operated under full load until the reservoir was replenished.

Less than a month after Oldsmobile launched the Jetfire, Chevrolet introduced the Corvair Monza Spyder in coupé and convertible versions. The Corvair’s U.S. rivals; the Ford Falcon, Plymouth Valiant, Dodge Lancer and Studebaker Lark, offered engines ranging up to 3.3 litres. The Corvair’s rear-mounted air-cooled flat six was only 2.4 litres, and customers were clamouring for more power.

Corvair Monza Spyder 2.4 litre turbocharged air cooled horizontally-opposed six cylinder powerplant

The turbocharger seemed to present an elegant solution. The Corvair engineers took what was to become the textbook approach to turbocharging in the decades to follow: they used a larger 76 mm turbo (this one supplied by TRW), a considerably higher boost pressure, and dropped the compression ratio to a detonation-resisting 8.00:1.

Monza Spyder engine cross-section

To further forestall the threat of pre-ignition while striving for maximum efficiency, they employed a novel system of controlling spark advance. The static timing was set at an amazing 24 degrees of initial advance with another 12 degrees of centrifugal advance coming in over 4000 rpm. Large degrees of advance generally equate to increased power and efficiency, so this was probably done to partially ameliorate the effects of the low compression ratio. To counteract this generous, but detonation-inducing advance, a vacuum diaphragm on the distributer provided not the usual vacuum advance, but pressure retard. Operating on a feed downstream from the turbo, this provided up to 9 degrees of retard, phasing in at 0.14 bar of boost.

Turbocharged Corvair Monza Spyder script

Unlike the current crop of turbocharged engines, the Corvair, like the BMW 2002 Turbo that followed, had no wastegate to limit the amount of boost pressure. Instead, like the original Volkswagen Beetle, they utilized an undersized carburettor to self-govern the engine. As a result, while very high levels of vacuum could develop between the carburettor and the turbo impellor, maximum boost at the intake ports was limited to around 0.83-0.90 bar. This was more than twice the boost used in the Jetfire, and the same level of pressure used in the original Porsche Turbo Carrera. The turbo boosted the power of the Corvair by 47% and the torque by 64%.

Unfortunately, the time wasn’t quite right for turbos. A turbocharger and a carburettor never make the best of friends, and 1960’s lubricant quality was not quite up to the high temperatures encountered by the turbo impeller bearings. The Jetfire was discontinued less than two years after it went on sale, and GM offered a no-charge retrofit kit that removed the turbo and all its plumbing in lieu of a four-venturi downdraft carburettor.

Most of the problems were do to the low level of boost and the aforementioned primitive quality of both engine oil and turbo-bearing technology. Because of the low boost pressure, the impeller was actually stationary at idle. If the owner failed to replenish the Turbo-Rocket Fluid (as many did) the closing of the auxiliary throttle would increase the likelihood of minimal impeller activity. The non-moving impeller would then often become frozen, the bearings seized by carbonized engine oil.

The Corvair Monza Spyder had a longer life, lasting nearly five years, until Chevrolet began the slow phase out of the entire Corvair lineup.

After the demise of the turbo Corvair, it would be seven years before motorists would be offered another turbocharged passenger car. In 1973 and 1974 BMW built a limited run of 1,672 turbocharged versions of the 2002. 1974 also saw the debut of the Porsche 911 Turbo, the first turbocharged vehicle to remain in production long enough to be properly developed. Among other refinements, it introduced the first intercooler. Potential oil temperature problems were largely sidestepped by the use of a prodigious 11-liter dry-sump lubrication system.

The impressive performance credentials of the Porsche brought the turbocharger glowing acclaim. Lingering issues like turbo lag were overlooked by buyers in awe of the acceleration and top speed figures. By the end of the 1970’s other manufactures began embracing the turbocharger as the public clamoured for cars bearing the “turbo” moniker and the first turbocharged diesel cars made their appearance at the close of the decade: the Peugeot 604 D Turbo and Mercedes-Benz 300 SD. Within a few more years, nearly every manufacturer offered at least one turbocharged model.

Today, while turbochargers on diesel-powered vehicles are ubiquitous, their popularity on non-diesels seems to have fluctuated with the price of crude oil. Now that fuel efficiency is back at the forefront, the spread of turbocharging in tandem with direct injection will likely expand considerably.

Here is an entertaining commercial shot in 1961 and aired in April of 1962 to introduce television audiences to the new Jetfire:

I wish BMW would have kept building the 2002 Turbo through the end of 1975 when production of the 2002 ended so there would be more used examples around today to choose from!

Interesting post. I knew of the Corvair Monza turbo, but did not know the Jetfire ever existed.

It is a shame about the early demise of the Corvair. When the second generation version came out for 1965, most of the problems had been rectified and the rear suspension (upper and lower A arm geometry using the axles as upper arms) was the same type as used on the E-Type and Stingray of the day. It was one of the best basic suspension designs you could get on a rear-engine car until the Alpine A310 in 1971.

GM has been a technology leader and doesn’t get much credit:

Cobalt/HHR SS, Grand National turbo engines

DOHC engines that made good power from Z34 Lumina, Olds Quad4

The small block V8 stands on its own as a technical marvel to the ZR1.

The new DI V6 makes 300 hp in the Cadillac and Camaro.

An economy car with a race head in the Cosworth Vega.

The Northstar made 300hp when 200 was a stretch.

The Camaro SS from the 90’s made over 300hp. Mustang only hit that with the 3v head in 2005.

The BOP 3.5 V8 was still used in MGs, Triumphs, Rovers, Land Rovers, TVRs, you name it up until a few years ago. A very good engine.

The bad- diesel engined Olds and the V4-6-8.

Interesting article. The Turbo-Rocket fluid sounds a lot like the urea injection for today’s diesels that no one will refill.

Great video! You don’t see commercials offering that much technical information anymore. Either the attention span of the public today is too short, or more likely, they just wouldn’t understand.

I too enjoyed the video. I don’t think the public is actually much interested in hearing about technology anymore. They just want to be fed numbers and buzzwords: 0-60, Number of speakers, Number of airbags, Direct Injection, Hybrid, etc.

In regard to JayP’s comment, I believe the first ‘economy car with a race head’ was the DOHC Ford Lotus Cortina of 1963-1966, introduced twelve years prior to the Cosworth Vega.

I saw a Lotus Cortina this last weekend. Nice car.

But for Chevy to bother with a twincam econo car? Pretty bold for the ’70s.

A friend and neighbor of mine back in 1966 amassed too many speeding tickets in his Corvette to the point where he could no longer afford his insurance premiums. He sold it and bought a brand new 1966 Corvair Corsa turbo (the top of the line in ’66) in a medium metallic blue. It was an attractive, impressive and fun car. The straight line performance was about on par with my ’65 289 2V Mustang but the steering and handling were far better. With the rear engine traction and IRS, he could also put the power down a lot better coming out of corners without worrying about wheel spin or wheel hop.

Pingback: Related Websites